In the decades since its production, most people have forgotten about Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate” and its harrowing production via the film ‘studio’ United Artists. Although this saga took place in the late 1970s, many of the mistakes made in the handling of that film are still relevant today.

The story behind “Heaven’s Gate” is still compelling because there weren’t necessarily clear villians. Michael Cimino, in a sense, was made to be the villain by many, but the truth was much more complicated. Unlike most film disasters though, “Heaven’s Gate” remains unique in that it directly contributed to the downfall of a major studio.

United Artists

Understanding United Artists’ history is essential to understanding why “Heaven’s Gate” created a perfect storm within the company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the partnership began with great optimism, but took decades to find success.

The real golden era for United Artists began when Arthur Krim and Robert Benjamin took control of the firm in 1951. That duo shifted the company away from being a formal studio, making it more of a financier and production company. They rented facilities and equipment from the other studios, allowing them to keep overhead light. Without an overhead burden, the company could take more risks than its competitors and those risks paid off through both critical and commercial success.

In the years immediately prior to “Heaven’s Gate,” United Artists had arguably been the most successful film company of the 1970s, winning the Oscar for Best Picture for “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” in 1975, “Rocky” in 1976, and “Annie Hall” in 1977. They also had massive commercial hits with the James Bond and Pink Panther franchises.

United Artists was acquired in 1967 by the giant conglomerate Transamerica. Krim remained with United Artists until the late 1978, when disputes with Transamerica over expenses caused him to lead an exodus of key executives. Those executives went on to form the rival Orion Pictures. In the meantime, a new team took over control at United Artists, including Steven Bach, who was eventually made co-head of production with David Field. Bach and Field would end up being the key executives in charge of “Heaven’s Gate.”

Introducing Michael Cimino

Michael Cimino came to prominence in the 1960s and early 1970s as a commercial director in New York, working on marquee Madison Avenue accounts. He had a reputation for being brilliant, but also difficult to work with. His commercials were known for an elaborate attention to detail.

Cimino became involved in Hollywood during the early 1970s as a screenwriter. Notably, he contributed to both the scripts for “Silent Running” and the Clint Eastwood film “Magnum Force.” His association with Eastwood continued when Cimino directed his feature film debut, “Thunderbolt & Lightfoot.”

While directing “Thunderbolt & Lightfoot,” Cimino was kept in check by Eastwood. Essentially, Eastwood would dictate the schedule to Cimino, refusing to do more than a handful of takes of any given shot. In this way, Cimino was kept on schedule and on budget.

United Artists became involved with Cimino as buzz was still building for Cimino’s next film, “The Deer Hunter.” The film had gone over budget, but many felt that the overages had occurred for legitimate reasons. After getting into a fight with Universal Pictures over the editing of “The Deer Hunter,” Cimino held numerous private screenings of the film in order to gain Hollywood support for his editing vision. The gamble worked and Cimino would eventually win Oscars for best picture and best director for his version of “The Deer Hunter.”

Proposing “Heaven’s Gate”

Cimino’s original proposal to United Artists was a film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s book “The Fountainhead.” United Artists wasn’t interested in his plans for that film, due to a perceived lack of marketability. However, United Artists did eventually agree to produce a film that Cimino had been trying to make for a number of years: “The Johnson County War.” In time, that project would be re-titled to “Heaven’s Gate.”

The story of “Heaven’s Gate” revolved around property clashes in Wyoming in the 1890s. Wealthy cattle barons who were bankrolled by east coast investors declared a pseudo-war on European immigrants. The immigrants had been granted land in Wyoming through the United States Homestead Act. That land grant ended up reducing the previously-available grazing land that the cattle barons depended on.

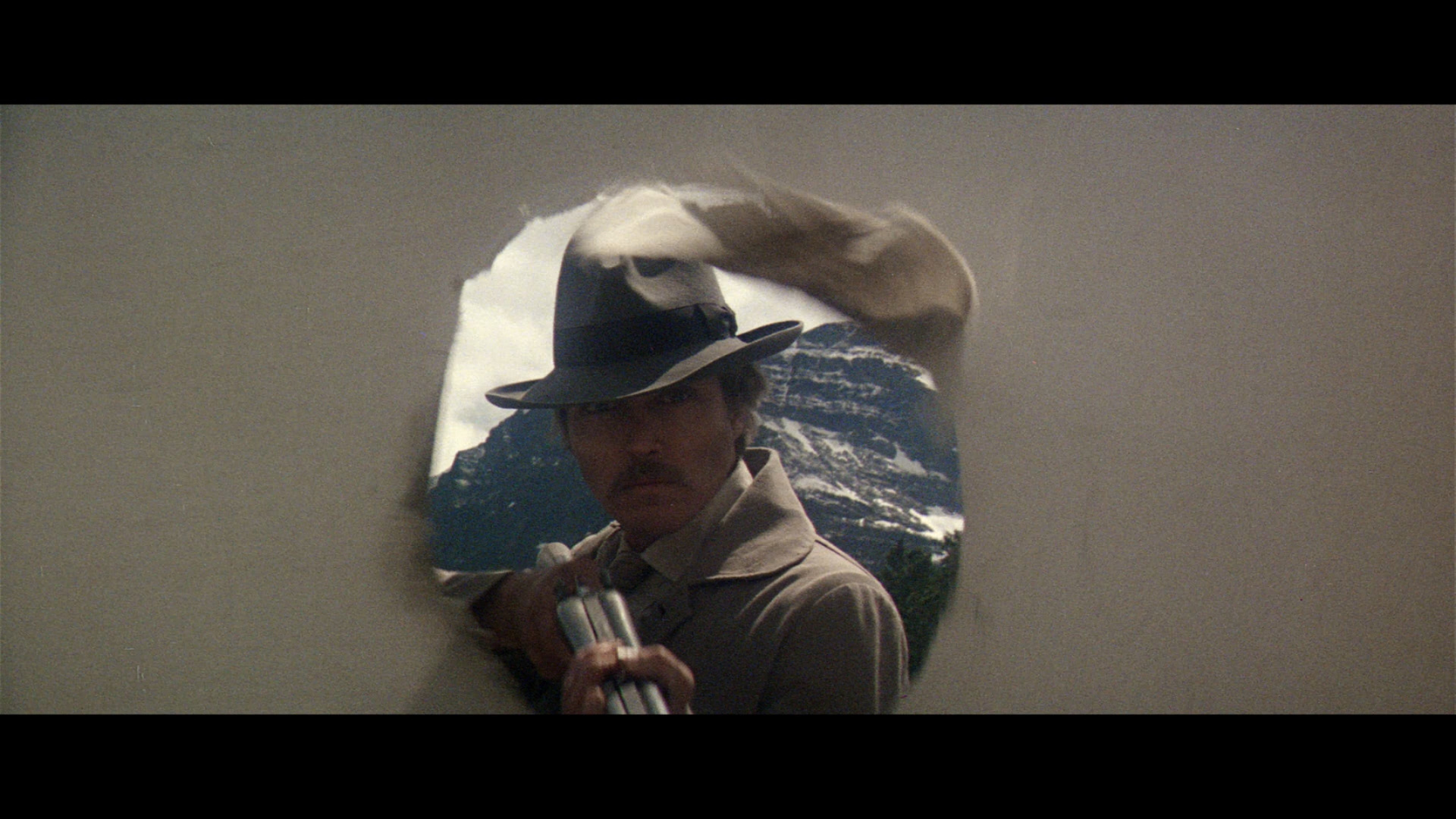

The final film featured a downtrodden sheriff rallying the immigrants to stand up against the bullying tactics of the cattle barons.

Deals & Casting

During Cimino’s initial interactions with UA, he came across to executives as charming. Yet, if the executives had paid more attention to Cimino’s run-ins with the press during publicity for “The Deer Hunter,” they might have noticed hints of things to come in his personality. In one notable interview, Cimino was called out by a reporter for lying about everything from his age to his military experience.

While working out the specifics of Cimino’s contract, several clauses threatened to derail his relationship with UA. In particular, this included a vanity title card in the film that would proclaim it ‘Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate.’ Cimino also insisted on full advertisement approval for the film.

Casting on “Heaven’s Gate” was hindered by a preexisting agreement that Cimino had struck with then-rising star Kris Kristofferson . Kristofferson’s contract guaranteed him top billing, a stipulation that ended up making “Heaven’s Gate” less appealing to the top female stars of the era, such as Jane Fonda. Unfortunately, many of the early financial projections that United Artists generated for the film assumed that a top female star would be involved.

Ultimately, United Artists executives found themselves in their first major showdown with Cimino over the casting of the actress Isabelle Huppert, who was then largely known only in France. Huppert’s plain features didn’t impress the United Artists executives nor did her heavy accent. Cimino won that battle though, using what would become a familiar threat. Time and again during conflicts, Cimino would suggest that United Artists could allow him to take “Heaven’s Gate” elsewhere, but United Artists believed in the overall film and didn’t want to let it go.

Budgeting & Pre-Production

United Artists’ initial budget estimates and faulty financial projections set the stage for later problems. Cimino’s original budget proposal was for a mere $7.5 million, a figure that United Artists didn’t entirely trust. They had their budget guru, Lee Katz, examine the numbers and he concluded that the film would actually end up costing $12-$15 million.

Cimino didn’t agree with Katz’s estimate, but United Artists allowed the project to move forward, internally assuming that Katz’s overage numbers would be acceptable to undertake if they occurred.

UA had a gap in their 1979 release schedule and pushed hard for “Heaven’s Gate” to be their Christmas blockbuster. The timing of the release played to Cimino’s ego, as it would allow the film to qualify for the 1980 Oscars. However, the timing meant an aggressive schedule, with the film not set to start principle photography until April of 1979.

Under the best of circumstances, what amounted to an eight month period of time would have been difficult for any film to be fully realized. Given that “Heaven’s Gate” was envisioned as a period epic, it seemed wishful thinking on United Artists’ part. Particularly since the film would be shot on location and complications such as weather-related delays all needed to be covered within what would only be a two-week buffer period.

This tight schedule was inadvertently the catalyst for Cimino’s later over-spending. In order to get Cimino to agree to the proposed release date, his contract included no punishment for overspending. Cimino’s contract also allowed him until the beginning of July 1979 to inform United Artists that a Christmas 1979 release would be impossible. From Cimino’s perspective, there were only upsides to agreeing to the aggressive release date, since he wouldn’t be punished if he couldn’t meet it.

Production

Over the months that followed, Cimino would be allowed to run his $7.5 million budget up to $34 million in expenditures. The final bill would later hit $44.5 million after all advertising and print costs were included. When considered in adjusted dollars from 1979 production costs, one realizes the staggering nature of a six to seven multiple overage.

It was not easy to spend that much money on location in Montana, but Cimino managed to do so by demanding an intense attention to detail in his production design and, more importantly, insisting on 40-50 takes for any given shot. Expensive touches included a particular period locomotive that needed to cross five states at a cost of $150,000 in order to arrive at the location site.

Production began literally days after Cimino’s “Deer Hunter” Oscar wins. That timing meant that the executives were hesitant to immediately question Cimino when he had fallen five days behind schedule by the sixth day of shooting. United Artists paid more attention when they received word on the twelfth day of shooting that Cimino had fallen ten days behind schedule.

When executives from United Artists finally visited the shooting location, they were shocked by what ended up being a four hour round trip daily driveto the location. They also encountered a more combative side of Cimino that would remain in place during the duration of the project.

Instead of reeling in Cimino, the United Artists executives were wowed during their visit by his initial footage. They were convinced that they had the equivalent of a classic David Lean epic on their hands. While they could have perhaps contained the disaster, they allowed Cimino to continue shooting into the summer unheeded. Even when the Christmas 1979 release plan was scrapped, Cimino continued shooting at his unexpectedly high cost levels.

Amid that madness, Cimino continued to handled disputes by repeatedly threatening to take “Heaven’s Gate” to a competitor for completion. Eventually, United Artists called Cimino’s bluff and no other studio stepped forward in a proposed partnership plan.

Despite the historic overruns in cost, the media had not yet publicized the “Heaven’s Gate” production story. The film’s remote location had allowed for a certain privacy. That changed in August of 1979, when an a local journalist named Les Gapay was refused an initial interview request with Cimino. Gapay ended up working as an extra and reported from inside the production. His resulting expose was sensational enough to be picked up by every major newspaper in the United States. Even at a time when the production was finally winding down, United Artists found itself having to fight a new war in the press. That initial bad publicity for the film would stigmatize it through to the release.

Principle photography that was initially scheduled to only last for two months ended up lasting seven.

Effecting Other Filmmakers

With Cimino going so far over budget, one less-obvious repercussion was the inability for other filmmakers to find money for their projects. Rival filmmakers grew jealous that Cimino’s budget overages were gobbling up money that had been previously set aside for several other United Artists films. When United Artists would eventually fall into a company-wide financial hardship, its demise cut the number of production options available to filmmakers in Hollywood.

Replacements & Setting Boundaries

Amid the initial spending crisis, United Artists considered firing Cimino and hiring a replacement director. That might have seemed like an obvious course of action, but doing so would have likely poisoned the film. Despite the challenges that the production encountered, Cimino was popular amongst most of the cast and crew.

United Artists feared that a new director would face issues with simply retraining that cast and crew, since key contributors might ‘walk’ from the production. The only way to make such a change successful would have been to select an equally-popular director. Unfortunately, such directors weren’t necessarily available or interested in the job.

United Artists finally regained control of the production of “Heaven’s Gate” when they began enforcing contract clauses involving Cimino’s ability to have final cut on the editing of the film. Cimino agreed to a revised schedule and revised budget, both still quite generous on the part of UA.

That final stretch of shooting went well enough that the Cimino was allowed to film expensive prologue and epilogue sequences that would help better frame the film’s story. In that case, he managed to come in on time and slightly under budget on those particular sequences. Somewhat too late, United Artists had learned that Cimino worked best within firm boundaries.

United Artists’ executives still thought that it would be possible for them to ‘save’ “Heaven’s Gate,” much like had been done during the lengthy production and post-production of Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” While similar on the surface, the situations with both films were not comparable once one examined the particulars. Coppola had faced a number of natural disasters and personally invested in his film. Cimino didn’t have the same direct financial stake in “Heaven’s Gate.”

Editing & Premiere

Given the large number of takes during principle photography, “Heaven’s Gate” went into the editing room with a then-record 1.5 million feet of film shot. Roughly 200 hours’ worth of footage needed to be cut into a film that Cimino was contracted to be less than 3 hours. When Cimino presented his first cut to executives, it ran an impressive 5.5 hours and caused outrage at United Artists.

The ultimate version of the film that premiered in New York in October of 1980 ran 3 hours 39 minutes. That screening was considered to be a disaster by many attendees. Critics went into the premiere with negative impressions already in mind and the audience apparently seemed bored from the film’s slow pacing. What should have been a celebration for the film was essentially its public funeral.

Handling Critics

Led by the New York Times critic Vincent Canby, critics seemed to almost try to one-up one another in their vicious reviews of the film. A further screening took place in Toronto, but the film’s Los Angeles premiere was cancelled.

As crazy as it might seem, Cimino publically responded to criticism with the following quote: “…certain journalists have been waiting to destroy me… Because I represent success and talent.” Such quotes only further angered the critical press.

Complicating matters, the press also attacked Cimino for the many historical liberties that he took when portraying the Johnson County War in “Heaven’s Gate.” Cimino had previously been criticized for his liberties with Vietnam in “The Deer Hunter,” so it was little surprise that the critics went after Cimino’s next film in a similar manner.

Re-Edit & Release

Given the negative reviews that resulted from the premiere, discussions of a re-edit began immediately. Film historians have pointed to this being a key mistake on the part of United Artists, as it gave public credence to the critics’ points. In the minds of the movie going public, the critics had been right and United Artists was admitting that “Heaven’s Gate” was a failure.

Cimino supervised the edit of a streamlined 2.5 hour version of the film, purportedly with an armed guard stationed outside of the editing room door. Tensions with United Artists staff remained high. The shorter version of the film was an attempt to improve the original cut’s pacing. It also used narration and title cards to clarify certain plot points.

United Artists did bring in a top consultant to help with the wide release of the film. He created a sophisticated plan that would have helped mitigate the disaster and turn the negative attention into something positive. That plan might have worked, had Cimino cooperated, but he again went rogue.

In particular, Cimino initially refused to be involved in press interviews due to a minor dispute over an outstanding $45,000 payment. He later surprised United Artists by agreeing in secret to a two-part interview with the Today Show’s film critic Gene Shalit. Shalit was brutal in his questioning, putting Cimino in a defensive position during most of their discussion.

Predictably, the formal release of “Heaven’s Gate” was brief. Cimino’s changes to the premiere cut weren’t enough to change the minds of critics. The film only grossed $1.3 million in its initial theatrical run.

Damaged Careers

Michael Cimino went on to make other films after “Heaven’s Gate,” but his career never entirely recovered. “Year of the Dragon” (1985), “The Sicilian” (1987), “Desperate Hours” (1990), and “Sunchaser” (1996) were all considered box office flops. None of those films received the same critical success as “The Deer Hunter.”

Within United Artists, none of the executives directly involved with “Heaven’s Gate” kept their jobs. Steven Bach had known that his career was over for quite some time, but had hoped that “Heaven’s Gate” might find enough box office success to allow him to resign with dignity. After being fired, Bach wrote his tell-all book “Final Cut” and largely went into the teaching profession. His firing took place on the eve of United Artists’ sale to MGM, as Transamerica decided to liquidate the firm. Bach was fortunate to negotiate a last-minute severance package.

Bach’s co-head of production at United Artists, David Field, left prior to the disastrous premiere of “Heaven’s Gate.” He essentially escaped before the firing began. Andy Albeck,the then-CEO of United Artists, was pushed out by Transamerica prior to the MGM sale.

After the MGM purchase, United Artists largely faded away. It was consolidated into MGM’s structure and essentially lived on as a brand only. Over time, MGM would run into its own financial struggles, but the legacy of franchises such as the James Bond series and home video exploitation of United Artists’ impressive back catalog of films lived on through licensing deals with healthier studios.

Conclusions

Much of what went wrong with “Heaven’s Gate” could easily happen again if a similar sort of ‘perfect storm’ were to arise within a studio. In fact, many observers thought that James Cameron was going down a very similar path with his production of “Titanic” – at least, until that film broke domestic and international box office records. Sometimes the risk can be worth the reward, but film history has been littered with more films like “Heaven’s Gate” than “Titanic.”

As with any good story, the story behind “Heaven’s Gate” featured heroes and villains who were not entirely black and white. No one person or group of people could be blamed for the disaster that occurred.

It’s a confusing situation to evaluate, because one often wants to side with the artist, but that was difficult when Cimino often seemed to go too far. Cimino was arrogant and irresponsible, but he also genuinely believed that he was making a timeless masterpiece that would be a point of pride for everyone involved.

At a macro level, the United Artists executives appeared to be ‘asleep at the wheel.’ The executives were weak, but most of their decisions were justifiable under the particular circumstances. When events were examined at a micro level, the various no-win scenarios that the executives repeatedly found themselves in were more apparent.

The critical media was justified in proclaiming that “Heaven’s Gate” was not a masterpiece, but they went overboard in trying to top one another when declaring the film a disaster. In particular, the New York press that reviewed the premiere cut of the film were so negative in their remarks that the film was only further harmed by the recut process.

It is undeniable that “Heaven’s Gate” had a major impact on Hollywood, although most of those repercussions were very negative for the entire film community. For all express purposes, the ‘auteur era’ of film that came into prominence in Hollywood in the 1970s ended with “Heaven’s Gate.” Companies became more focused on controlling costs and not allowing directors as much freedom.

Surprisingly, Cimino slowly enjoyed a re-evaluation of “Heaven’s Gate.” These surges in acclaim have mostly come from European critics and began as far back as 1982 into 1983. Granted, there were accusations that the European critics gushing over the film merely did so as a shot at the American critics who loathed it. That turning of the tide in public opinion seemed to be the only explanation for why Cimino was allowed to direct future films. He had, after all, bankrupt a studio.

In the 2000s, re-evaluation of “Heaven’s Gate” surged again, with it playing well in a 2005 re-release. A slightly-tweaked version premiered at the 2012 Venice Film Festival to great acclaim. Later that same year, that version screened at the New York Film Festival. Both Cimino and star Kris Kristopherson were frequently applauded during a post-film Q&A. Several weeks later, the Criterion Collection, known for creating ‘special edition’ home release of significant films released the revised film for home viewers.

- “Masters of Doom” by David Kushner - December 16, 2023

- San Diego Comic-Con 2023 Analysis - July 29, 2023

- Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019) Reviewed - March 15, 2023

3 thoughts on “Lessons Learned from Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980)”

Andy ALBECK. Norbert AUERBACH. Get it right.

Thanks for the correction – I’ve fixed the error.

Studio Remarkable comes through again with a superb breakdown of the intricacies of this project.